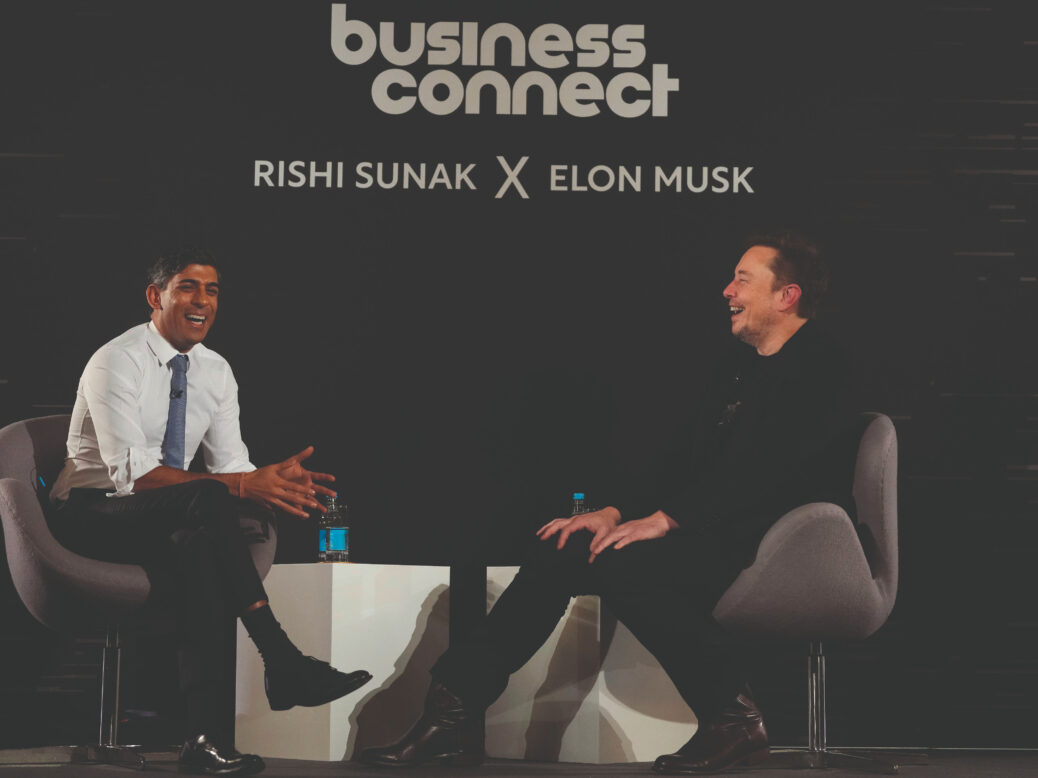

The government spent months trailing its AI summit – the UK’s assertion of its relevance to the global debate on how to regulate the technology of the moment. But the resounding image from this month’s meeting was of Prime Minister Rishi Sunak interviewing Elon Musk. With a series of softball questions, Sunak and the richest man in the world had a quasi-philosophical discussion about how AI could make humans obsolete.

And yet, despite the existential concerns over artificial intelligence, the Prime Minister seems in no hurry to act. Ahead of the conference at Bletchley Park – the location of Allied code-breaking in the Second World War – Sunak said that the government would “not rush” to regulate AI, though he did announce the creation of an AI safety institute, tasked with researching and testing new technologies.

During Sunak’s speech at the summit, the word “regulation” was not mentioned once. Meanwhile, the European Union’s AI Act and the US’s Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights are already under way.

Following the summit, Keir Starmer accused Sunak of “fanboying” over Musk – who, alongside wealth, wields significant political influence because of his ownership of what was previously called Twitter – rather than drawing firm red lines on nascent AI technology. But what would Labour do differently if it wins the next general election? The Tories are “starry-eyed and subservient” towards the tech sector, Kirsty Innes, director of technology policy at the think tank Labour Together, tells New Statesman Spotlight, while Labour’s approach is “much more down to Earth”.

There is a real opportunity for the party, says Innes. “[Rather than] concerning [themselves] with what’s going on in Silicon Valley or what might happen in 50 years’ time, there is a clear determination to make improvements to people’s lives here and now.”

A recent survey from Labour Together found that the public’s main concerns over AI are immediate: the spread of misinformation, job losses and the use of AI to monitor or control people at work.

In the shadow cabinet reshuffle in September, Labour mirrored the structure of the government after it split the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport into two distinct entities. Peter Kyle, shadow secretary for the new Department for Science, Innovation and Technology, has since announced several policy interventions. These include regulating developers of “frontier AI” – the most advanced general-purpose AI models – with requirements around reporting, safety testing their training models, and ensuring security is in place to limit the unintended spread of dangerous tech.

Labour also plans to set up a Regulatory Innovation Office – a “pro-innovation” body to expedite regulatory decisions; ten-year research and development (R&D) budgets to encourage longer-term investment into technology; and Skills England, a new body to meet UK skills needs, as well as reforming the Skills and Apprenticeship Levy to focus it more on training young people for “modern technological demands”.

Kyle tells Spotlight that by working in partnership with the private sector, “science and technology will have a central role in delivering Labour’s five national missions” – economic growth, green energy, an NHS fit for the future, tackling crime, and increasing opportunity. For example, the new Regulatory Innovation Office would speed up the roll-out of new technologies, and would be applied in areas such as clinical trials to get new medicines to NHS patients more quickly. The ten-year budgets for R&D institutions would unlock private sector investment in key industries through longer funding cycles than those the existing public body, UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), offers.

“The AI summit was an opportunity for the UK to lead the global debate on how we regulate this powerful new technology for good,” Kyle says. “Instead, the Prime Minister has been left behind by the US and EU, who are moving ahead with real safeguards on the technology.” Kyle adds that the party’s plans for regulating AI and tech “will build public trust and deliver security and opportunity for working people”.

[See also: Voters don’t share Rishi Sunak’s easy-going approach to AI]

Industry sources tell Spotlight that technology is increasingly becoming a policy priority for the party, with many members of the shadow cabinet having “tech literacy” – such as Darren Jones, shadow chief secretary to the Treasury, and Alex Davies-Jones*, shadow minister for tech and digital economy, respectively the past and current chairs of the think tank Labour Digital. “Tech had fallen between the cracks for Labour, but since the appointment of Peter Kyle, it’s a good sign for the industry,” says Neil Ross, associate director of policy at TechUK.

But the party has not laid out a full position on regulation, including whether it would create an independent regulator or give new powers to an existing one, such as the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO). The former shadow digital secretary Lucy Powell suggested making AI a “licensed” industry, like medicines and nuclear power. An industry source tells Spotlight that licensing has been discussed among Labour frontbenchers but warns that this would need a “tiered approach” to ensure smaller businesses are not disadvantaged.

Labour should look to “set a regulatory environment which is supportive of innovation and agile enough to keep up with the pace of change”, says Innes. The Online Safety Act has become law six years since it was first conceived, in which time social media has changed immeasurably.

“You need more agile regulators, and you need a better, more flexible approach,” she says. But “regulating complicated and fast-moving industries isn’t a wholly new science”, and lessons can be taken from sectors such as financial services, where “sandboxes” are used to support innovation while mitigating risk. These are controlled environments that allow businesses to test new products with oversight by a regulator.

The need to legislate AI is urgent, says Michael Birtwistle, associate director of law and policy at the Ada Lovelace Institute, given the “unusually fast” pace with which it is being adopted across society. “It’s much harder to regulate something after it’s integrated into economies, as we’ve seen with social media,” he adds. Without legislation, developers will not be incentivised to build in safety, and consumers will have fewer rights of redress when things go wrong. An incoming government could also learn from existing regulation, he says – self-driving vehicles already have far more robust safety laws than comparable autonomous systems.

Major incidents where tech went wrong, such as scandals over Cambridge Analytica or the Ofqual exams algorithm, have damaged trust: robustness and transparency is vital to rebuilding that, says Kriti Sharma, chief product officer of legal technology at Thomson Reuters.

There are easy wins, such as adding a kitemark on online chats to indicate whether someone is speaking with a human or a robot, and adding source citations for information produced by AIs. More complex solutions include ensuring AI models are trained on diverse, trusted data sets. Regulation should follow the “high bar” set by other high-risk industries, such as law, financial services and health, Sharma says.

“To not put legislation in place is to gamble on trust being lost,” adds Birtwistle, as well as “us not being able to deploy and use that technology fully, and people not being willing to share the data necessary to train those technologies”.

[See also: The Research Brief: What the AI summit should have focused on]

Skills gaps and a lack of new talent are some of the biggest issues facing the industry, while job losses are a key concern for the public about AI. Polling from BMG Research found that more than half of 18-24-year-olds are worried about the impact of technology on their future employment prospects. While industry sources tell Spotlight they were broadly pleased to see Labour focusing on specialist training through Skills England, Victoria Nash, director of the Oxford Internet Institute, says she wants to see the party embed digital literacy across the whole school curriculum and tackle digital exclusion. “Digital inequalities don’t support great education outcomes,” she says. If Labour is “keen on levelling up”, the party should look at issues such as getting children out of data poverty, and getting better access to loan devices through schools, she adds.

Tech skills can boost productivity and “unleash human potential” to improve society, as well as contribute to the economy, says Sharma. For example, an AI assistant could help lawyers draft documents more quickly, freeing them up to do pro bono work. An incoming government should hold itself to account with “hard numbers”, she says, setting targets for increasing productivity levels, skill-level improvements, and new jobs generated.

To be globally competitive, a Labour government will need to work in partnership with the tech industry. The plan for ten-year R&D budgets shows that Labour is “listening and engaging with the sector”, says TechUK’s Ross, but the party could go further by exploring collaborative taskforce models. For instance, TechUK runs an online steering group, made up of representatives from the tech and banking sectors, regulators and the government, which convenes to create solutions to tackle fraud. The partnership has helped to reduce online financial scams “without having to default to slow-moving legislation or complex regulatory consultations”.

Labour also has a huge opportunity to transform public services with technology, says Innes of Labour Together. While the rest of the economy has adopted tech rapidly, government services still seem slow and outdated by comparison. “Labour’s ambition should be to make it so that the public sector is equally as ambitious and innovative when looking for ways to serve citizens better, as the private sector is in serving its customers better,” she says.

Most of all, an incoming government should focus on learning from experts in the field. “Listen more to the people building [AI],” says Sharma. “Don’t get fascinated by tech celebrities or headline-grabbing messages. Whoever’s coming in next has a once-in-a-generation opportunity to drive real change.”

This piece was first published on 24 November 2023 in a Spotlight special print edition about Labour policy. Read it here.

*Since publication, Alex Davies-Jones has changed role from shadow minister for tech and digital economy to shadow minister for domestic violence and safeguarding in a shadow cabinet reshuffle.

[See also: How AI is speeding up diagnosis]